The Epic Story of the Dutch Tulip

Some Reading For The Flight, The Dutch Tulip…

I wrote the following article for people who’re coming to Holland to see the tulips. The idea being that you have a long flight and some hours to kill, and I thought I might keep you occupied with a relatively long read about the history of tulips in Holland.

Click this link for more info about our Tulips Tour: Keukenhof Gardens that runs in 2020

THE EPIC STORY OF THE DUTCH TULIP

by Rory Brosnan

When you land at Schiphol Airport and start to make your way to Amsterdam the souvenirs they try to sell you will take the form of (miniature) windmills, clogs, and tulips. Of these, it’s just the tulip that retains a significance in Dutch life that is not purely sentimental.

I have farmer friends in the Beemster who might strenuously object to that statement. Occasionally when I bring one of our small tour groups there, they’ll be going about their work on the farm with a pair of clogs on their feet. However, they’re always just a bit too ready to explain how practical clogs are (they do keep your feet remarkably dry, and the grip isn’t really an issue on the flat, boggy land). And you just won’t see wooden shoes being worn on the streets of Amsterdam or Rotterdam…. Or Utrecht, Haarlem, Alkmaar, Zwolle or Maastricht.

It’s true that you can find windmills today being harnessed just as they were in the 1600s, but it’s very much an exercise in Dutch heritage. It will be the product of a non-profit organization and their volunteer millers who’ve banded together to protect the local heritage. These windmills could stop turning forever and the loss would accrue only to the Dutch psyche.

The tulip, however, is a far more vital icon. Yes, it’s an elegant flower and an easy sell to tourists but it’s also a major Dutch export and is significant in the balance sheets of businesses and farms countrywide (you’ll forgive the lack of sentiment but I’m just mimicking my hosts).

If you’re reading this it’s quite likely you’ve planned a trip to Holland to visit the Keukenhof Gardens. It’s one of the biggest tourists draws in the country, attracting 1.2 million visitors annually to its expansive, beautiful gardens. But it’s slap bang in the middle of tulip country, surrounded by real, working tulip farms. You’ll drive by fields that stretch for hundreds of meters and are resplendent with shocking pink, crimson, purple and yellow blooms.

The Dutch are some of the warmest, most down-to-earth people you’ll meet, but these qualities are cloaked behind a pragmatic, gruff exterior. I like to think that the national penchant for multi-colored tulip fields in Spring is their joie-de-vivre subliminally rising to the surface.

Anyway, maudlin theories aside let me return to the tulip. Though it thrives in this flat, boggy nation it is not of it. It originated in a region that is the complete opposite of The Netherlands, a place so mountainous, elevated and hard to explore that it meant ancient Rome and China did not know of each other.

The tulip originated in the mountains of Central Asia. Let me tell you the epic story of how it has come to be echt Nederlands.

*****

In The Beginning

The Tien Shan mountain range runs along northwest China and meets the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan – two countries probably better conjured in the Western conscious as southern areas of the former Soviet Empire. These two mountain ranges meet and form a barrier thousands of miles long, hundreds of miles wide and some miles high. It’s a vast and craggy wilderness. The terrain doesn’t yield crops. In summer it’s baking hot and in winter it’s icy cold. This is where the tulip came from.

These ancient tulips were a little different from the proud, elegant varieties you’ll purchase from a florist today. They were shorter and more compact, all round more basic, but still beautiful in a primitive way. Though these varieties were predominantly red there was a lot of variation amongst the actual flowers.

These flowers were hardy and adaptable. In winter they would hide from the cold underground – in bulb form – and then bloom in Spring. Summer would roll around and once more they would retreat underground, this time hiding from the heat.

The area wasn’t totally impenetrable. You could find an occasional obscure passage that would allow you to pass for a month or three in summer, and there were sometimes areas of oases. Over time nature spread the tulip to a certain extent – to the north until it met harsh Siberia and to the south where it met the Himalayas, and perhaps skirted a bit into the nooks and crannies of Asia, making its way down to the Arabian sea.

However, thousands of years ago warring tribes and nomads were what really helped the westward migration of the tulip. The tulip made its way to Persia, India, further north to the Crimea, and even as far west as Crete. Those are largely Islamic lands and in that religion, paradise is often imagined as a garden. Christian scribes allude to a shining city on a hill but their Muslim equivalents envisage a perfect garden, one full of beautiful flowers.

The tulip became venerated in the early Islamic period. In addition to being beautiful and elegant when it’s in full bloom, its head appears to be bowed. It symbolized holiness and obedience.

We can say with certainty that by 1050 tulips had come to be venerated in Persia. Tulips grew in the gardens of the old capital, Ishafan, and also Baghdad. Poets of that general era used the tulip as a metaphor for beauty and female perfection. One poet, Musli Addin Sa’adi, describes his ideal garden in 1250 as a place where “the murmur of a cool stream, bird song, ripe fruit in plenty, bright multi-colored tulips and fragrant roses” combined to create paradise on earth. And with red being a predominant color of these tulips, it also lent itself to images of blood, sacrifice, and passion.

Of the tribes who carried the tulip west, the most significant were the Turks. Before researching this story I assumed that the Turks were from Turkey. It’s a fair assumption to make (right?) but originally they were a nomadic tribe and only eventually settled in Anatolia – modern-day Turkey – in the 11th century.

The Turks venerated the tulip-like no other. As nomads who perennially had to survive harsh Asian winters, they would have seen these flowers blooming in Spring and seen not just beauty but endurance. The Turkish word for tulip – lale – uses the same letters as the word for Allah.

Constantinople was quite the glittering prize of bygone eras. A magnificent city, it was the capital of the Byzantine Empire until the Turks captured it in 1453. The city was in a state of decay, but by then the Turks had been stationary for 400 years and they must have liked the idea of a fixer-upper for they restored it magnificently and made it their capital.

The setting of Istanbul is quite idyllic. It was built on seven great hills – right at the point where Europe and Asia attempt to touch hands – and is bordered on three sides by water. New buildings appeared on the skyline. Four huge minarets were added alongside the cathedral of St. Sophia. The most magnificent of the new builds was a palace with the fanciful title, the Abode of Bliss (today it is known as the Topkapi). In order to reach the inner sanctum, where the Sultan enjoyed his private life, a visitor had to go many levels deep. A thoroughfare brought you to a plaza and the large palace walls and gate. This led to the first of four great courtyards, each more sacred – and inaccessible to commoners – than the last.

Governance and administration of various hues took place in these courtyards and buildings, but the final one was the most inaccessible, the most elite, and no governance took place there. It was where the Sultan took his pleasure and contained the imperial gardens. A kind of paradise on earth. The Abode of Bliss was so extensive that the Sultan employed 920 gardeners to tend to the grounds. This was a more exalted position than it sounds – the gardeners doubled as executioners and the head gardener was the head executioner… There’s a metaphor in there somewhere about the cycle of life.

Such opulence wasn’t the domain of ordinary folk in the Ottoman Empire, but they certainly shared the love of the tulip. Excess flowers from the Sultan’s gardens were charitably offered for sale to commoners at the market, and all over the empire, the tulip adorned prayer rugs, robes, tiles, and flower vases.

The history of the Middle Ages with its bloody battles and murderous family feuds often makes it seem like a time of unrestrained barbarism. There was, however, diplomacy and occasional accounts of intrepid travelers who ventured far afield just to see other cultures.

By the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire was firmly established as a dominant power. Right on Europe’s doorstep, Western powers stationed diplomats there and it also received a small smattering of medieval tourists. These men (they were almost exclusively men) would have seen tulips and images of tulip all over Istanbul and throughout the Ottoman Empire, and it would have been via these travelers that the first bulbs made it into Western Europe. By the 1550s the flower had been spotted in the likes of Augsburg, Padua and Venice. There are various claims on who exactly brought the first bulb but, alas, we can’t resolve that squabble.

To The North

Let us jump now to Northern Europe and the year 1562. This is a place of trade, merchants, ledgers, and incremental growth. You could say that it was the cradle of modernity. There was less of war and more of accounting round here. Just up the road (or coastline if you prefer) in a few decades people would depart from Amsterdam and colonize the island of Manhattan.

Anyway, a ship has docked carrying a cargo of cloth from Istanbul. We don’t know the name of the Flemish merchant who ordered it, but let’s call him Lodewyk van Artevelde (‘cos it just seems to fit). Profit, profit, profit, he must have been thinking as he descended into to hold and started inspecting his merchandise.

And then he noticed an extra little package. He opened it up and discovered a parcel of Turkish onions. “Jolly nice one”, he might have thought in a way that isn’t remotely Flemish. He finished up and then set off happily for home with his little gift tucked happily under his arm. We’re not sure what he had for dinner that night, but as a man of means he would probably have had meat, and let’s just say it was a rabbit, for there was a local breed of massive rabbit called the Flemish Giant. His servant seasoned the unusual onions with oil and vinegar, popped it into the roasting dish and cooked it up along with the rest.

Lodewyk enjoyed the taste of the Turkish onions and had had the foresight to keep a few of them aside. He planted them in his garden, right next to a bunch of cabbages. Months rolled by and in Spring 1563 when something started poking out of the ground he was a little disappointed to find, not a new batch of Turkish onions, but a rather large and elegant flower. These were the first tulips in Northern Europe.

A day or two later he was visited by a friend, a keen horticulturist, who confirmed that this was, in fact, a whole new species of flower. They were both a tad excited. Like a game of whispers, this friend had a friend who was an even keener horticulturist. In fact, this second man would go on to become one of the most influential botanists of all time. His name was Carolus Clusius.

The dominant figures of history often seem like predictable caricatures. Men whose sole function was to join or under an empire, and whose entire existence seems given over to the ploys and ruses of power. It’s at the footnotes of history where we see men and women who seem more human, more possessed of a fully formed personality with foibles and idiosyncrasies. Clusius was one of those.

He was born Charles de L’Escluse in 1526 in the French city of Arras. Right about the time, Protestantism was challenging Catholicism for primacy in Europe. Clusius jumped religious ship, converting from the latter to the former. It seems to have stemmed from humanist beliefs, and not theological dogma. He seemed to just like books, study and the world of the mind (and nature). Men of his ilk in academia often took a Latinate name, harkening back to the scholars of antiquity.

Clusius first studied law, which he wasn’t overly enthused about. He’d take long walks in the woods and found himself fascinated by the flora he saw. Plants had only ever been valued for their medicinal and nutritional value but Clusius felt they were intrinsically important. He started to document what he saw, and then went the whole hog and chucked in his study of law and became a botanist. His father wasn’t happy – are parents ever when you give up a sensible legal career for some newfangled area of study?

Clusius was a kindly, avuncular figure. He spent his career traveling around Europe – variously collecting flora on his travels, and then settling down for a period for a job so that he may try to pay his way. Invariably he fell on hard luck and bad times. A plum appointment to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian (who, as Voltaire pointed out, was neither Holy nor Roman and only nominally an emperor) saw him being victimized by the Emperor’s Catholic chamberlain – the man in control of paying wages. And when Maximilian died suddenly, a Catholic, Rudolf II, replaced him and Clusius was out on his ear.

This was emblematic of Clusius’ life. But he always soldiered on, an endearing figure with a singular love of plants and knowledge. He was almost forty when he saw his first tulip bulbs – the ones that Lodewyk van Artevelde’s friend sent to him. Clusius planted them, watched them grow, studied them, and documented them.

Clusius was fluent in nine languages and had friends far and wide, and sent almost 4000 letters in his lifetime. It helps explain why he flirted with poverty all his life. A stamp today costs about €1 but back then it was expensive to post a single letter, not to mind thousands of them.

Clusius sent tulip bulbs to other botanist friends to study, and they and their friends, in turn, sent different tulip bulbs back to Clusius. In this way, the tulip was distributed further around Europe and he got to build up the largest collection of tulips in Europe.

Finally, in 1593 when Clusius was in his 60s good fortune solidly came his way. Leiden University had been established in 1572 by a newly formed country. Seven provinces in the Lowlands had broken from Spanish rule and became the United Provinces. Today we know it as The Netherlands. The battle was brutal and bitter and would drag on in one form or another in a struggle called the 80 Years War, spanning 1568 – 1648. It was a bit of a catchy marketing title, as the opening salvos possibly started a year or two either side of 1568, and there was a 12-year truce in the middle.

What we now know as Belgium and Luxembourg remained Catholic and under Spanish rule, while the United Provinces turned Protestant and declared independence. And they wanted a proper, prestigious university of their own. Which in turn meant they had to headhunt Europe’s finest academics and for botany, they chased, and got, Clusius.

For his nice, stable salary Clusius was tasked with establishing a botanical garden to rival that of the University of Pisa and delivering lectures to students. The lecturing he didn’t care for at all, and he had reached a point in his life and career where he could essentially say, “stick it up yer arse”, and so he just didn’t bother to give any lectures.

He devoted himself to the botanical garden – all sorts of plants, not just tulips. And then as a hobby, he started his own private garden, which was primarily devoted to tulips. Because when you’ve spent all week in botany what you need to unwind is a bit of botany.

And so it was that Clusius advanced into his dotage with this wonderful sinecure in place and he was able to become the guardian of Europe’s greatest collection of tulip bulbs. He wasn’t the only botanist studying tulips, just the foremost. He and his cohorts learned all about it. It takes a single flower at least six or seven years to grow to maturity from seed, and this flower might vary greatly from its parent. However, a fully grown flower will also produce one or two offsets – miniature bulbs that can be planted, and grow to maturity in just a year or two. A parent bulb can only do this one or twice before dying.

The tulip had evolved considerably since it first began its journey from the mountains of Central Asia. The gardeners of the Ottoman Empire had latterly tried breeding the plant, and this had resulted in the advent of some new varieties. Now, botanists in Northern Europe started doing the same. It wasn’t understood how a new variety came about, but people tried things that seemed quite logical at the time. They cut differing bulbs in half and joined halves together, or they gathered pigeon dung and used it as soil.

The reality was that different varieties of wild tulips never grew together and in Europe, they were often side-by-side in flower beds, and it was but a short jump for an insect to cross-pollinate. This resulted in striking, unusual varieties. And additionally, sometimes a flower “broke”- a bulb that had previously produced a single-colored flower now produced a flower with unusual patterns.

(This process would not be understood until the 20th century when it was learned that these beautiful and exotic freaks were the result of a virus carried by the humble aphid).

Fashionistas

Rich people have always needed symbols to show their status and Porsches hadn’t been invented then so they fastened upon rare and broken tulips. Clusius was generous and he readily shared his bulbs with friends and other botanists. Now, he started to get requests from more strangers, and strangers of a dubious bearing. They were profiteers who wanted to sell his bulbs on to some aristocrat or other and pocket a healthy profit.

Clusius always refused to sell to these people. Not primarily because they were sneaky but because they – and their clients – knew nothing about tulips. However, what they couldn’t buy they were happy to steal, and twice he woke up in 1596 to find that his beloved garden had been ransacked in the middle of the night. And then finally in 1598, there was another nocturnal theft and his remaining stock was gone.

He was 72 at that point and his life’s work had just disappeared.

The rare varieties were especially popular amongst the Flemish aristocracy of what is now Belgium. From there it was a short jump to France and in around 1610 the tulip caught on spectacularly in the Royal Court of France. The fad lasted just a few years in Paris, but it helped spread the fame of the tulip to the regions and provinces of Europe.

The French made the tulip fashionable but the Dutch made it profitable. Clusius’ stolen bulbs became the starting stock of the tulip fields that sprang up around Haarlem on the North Sea and southwards towards Leiden. These are the same fields you might drive past as you visit the Keukenhof Gardens and they were what supplied the connoisseur market in the early 1600s. Though Clusius died disillusioned, the thieves did his work for him and his legacy was literally planted far and wide.

The Dutch Golden Age in the 1600s was based wholly on their talent for trade. Theirs is a waterlogged country, with few natural resources and in order to first survive, and then thrive, they made themselves the middlemen of Europe. That was initially in the 1400s and 1500s, and then around 1600 they followed the Spanish and Portuguese around the world.

They dominated the trade routes from the Far East. Though they weren’t interested in conquering lands like other European powers, their appetite for the local produce left the local tribes and populations no better off. Profit was their goal, and they profited maximally from the rich trades as it came to be known.

Their knowledge of market dynamics was keen, and there was a market for tulips. Uniquely, they could actually grow them themselves. All the better than to need to provision a ship and sail it halfway around the world. It takes seven to ten years for a crop of tulips to grow. It’s a slow rate, but as time passes the aggregate crop does increase. The tulip fields slowly pushed south and north of Haarlem.

Though the 80 Years War formally finished in 1648 it brought with it great cultural and social change long before that point. The Protestant United Provinces declared themselves independent in 1581. The Spanish monarch, Phillip II, was austerely Catholic and there were periodic purges of Protestants from the remaining Lowlands in the early 1600s.

The United Provinces accepted these refugees. There were many rich merchants amongst their ranks and they brought with them wealth, trade contacts and industrial know-how. For their part, the Dutch officially outlawed Catholicism but allowed it to be easily practiced behind closed doors and didn’t expel any Catholics. The new country got richer. Some of these migrants brought with them great knowledge of tulips and more actual tulips. This swelled the number of tulips in circulation and the Flemish love of the flower caught on amongst the Dutch themselves.

There was no monarchy to be seen in The Netherlands. The ruling elite was the regent class. This consisted of families that had grown rich from trade in the 1500s and continued on in the 1600s, and men who had become rich through trade in their own lifetime. There were perhaps a few thousand of these people. It wasn’t exactly democracy as know it today, but it was far more egalitarian than the monarchies of France, Spain or England.

These rich merchants all had fancy houses, and if you had a fancy house you almost certainly had a fancy garden too. This necessitated, in many cases, having the best, most expensive flower to adorn it. The tulip.

As Dutch regents came, none were more puffed up and wealthy than Adriaen Pauw. His father had amassed great wealth by shipping salt and grain from the Baltic, and then bolstered it by being one of the largest initial investors in the Dutch East India Company. Adriaen followed in his father’s financial footsteps and also became a key political player amongst the Dutch elite. He was made Grand Pensionary – or governor – of the province of Holland. There were six other provinces in the country, but Holland was the most important one and he was effectively Prime Minister of the country.

In the 1620s he renovated an old castle just outside Haarlem and had it made into the grandest house in the land. It was so tall that on a clear day you could see all the way to Amsterdam, some 15 miles away.

Of course, he also had the grandest garden. Lines of trees punctuated the decorative lawns and the flower beds were filled with roses, carnations, and lilies. Their magnificent colors framed perfectly in the formal beds. In the absolute center of the garden, was the flower of flowers. Tulips. Not just any type of tulip, of course, or even an impressive variety. But the rarest and most valuable, Semper Augustus.

Imagine yourself a scruffy local in that bygone era. Your younger siblings are street urchins, your father is at sea and your mother works 16 hours a day bleaching linen. A massive new house had been built on the edge of town, and you find yourself impelled to go and take a look. You’re not supposed to, of course. You’ll be prosecuted if found trespassing, but you do it anyway.

You break into the grounds, marvel at it all and then make your way deeper and deeper into the garden until you can see the exotic, fabulously expensive flower, the Semper Augustus tulip that everyone is talking about. There are hundreds of them.

Well, there appear to be hundreds of them. At a closer look, you see that there is a strange wooden contraption sunken into the bed. It has mirrors in it and where you thought there had been hundreds of tulips, there are actually only 10 or 20 flowers, and they’ve been reflected many, many times to create the illusion.

Adriaen Pauw could afford everything but he didn’t get to have everything.

*****

The Hoi Polloi and Tulips

Though the country in the Golden Age was wealthy and the history books recount the grand canal houses of Amsterdam, the paintings of Rembrandt and the spectacular (though ill-gotten) gains of the Dutch East India Company the reality for most Dutch people was far more squalid.

For ordinary people, the working day began before dawn and ended after dusk. Whether you were a blacksmith, a cooper or a maid you routinely worked 16 hours a day, and you subsisted on snacks of cheese and raw herring. Dinner was generally the national dish, hutspot, and it consisted of chopped mutton, vinegar, parsnips and prunes boiled in fat. It was supposed to stew for three hours but this was often reduced to one, and many times the meat could be rather expendable. A home was a cramped one or two-bedroom house and the rents were high. People had many babies but the infant mortality rate was very high.

As grim as all this sounds, what these ordinary Dutch people had that other Europeans did not was the possibility of social mobility. It didn’t happen very often, but it wasn’t impossible that someone could improve their wealth and status.

Trading a lump of your current wealth for a share of future profits in business was not a new concept, however, for the first time in history, this financial device was made available to the public. Amsterdam built the world’s first stock in 1611 so that shares in the Dutch East India Company could be traded. A lowly cooper or fishmonger could purchase stock – as long as they had the money. (Not coincidentally, the limited liability company was innovated at this time by Dutch traders).

You would labor all year and if misfortune hadn’t befallen you and your family, on a salary of 300 guilders you might be able to salt away 20. This was your annual savings. It was meager and could disappear in an instant. And if you did buy a share it was just one share whereas the regents held thousands.

Enter tulips.

There was a profitable market for these bulbs. The supply of tulips was limited, which meant you could charge high prices, and although the crop grew slowly, it did grow. You just needed time. Set the bulbs down in winter, see them bloom in Spring and then cash in. Additionally, you could try to achieve alchemy and induce a break in tulips by splicing bulbs together, growing them in pigeon poo and other such hopeful but failed attempts.

Crucially you didn’t need a lot of land, not even an acre. Tradesmen could mortgage their tools and take out a loan to rent or acquire a little patch of earth on which they could grow a few valuable bulbs. Or perhaps you did a little deal with a landowner – no rent up front, just cut him a share of the profits. Or the aforementioned 20 guilders in savings might suffice, especially if you had a few years to dip into. This is what common folk started doing. Not all of them or even many of them, but enough did it and the more that started doing it, the more that followed.

There were also people who roamed the countryside searching for unusual varieties that they would then sell to affluent collectors. They were called rhizotomi, which means root cutter in Greek. They weren’t always the most honest of people – it was quite easy to promise that such and such a bulb would yield an amazing flower as they would be long gone by the time the tulip bloomed.

In time though these grifters were found out and they were replaced by an emerging band of reputable professional or semi-professional growers. They were predominantly based in Haarlem, growing small plots of tulips just outside the city walls. The soft sandy soil nurtured the bulbs beautifully and an industry was growing.

There was one more piece of the puzzle: Advertising. You might think that in an era of such basic technology – no Internet, TV, photography or radio – that advertising would not be in play but you’d very wrong. If you were selling to the luxury market you really needed buyers to be able to visualize the flower they were buying, and luckily this was the greatest age in Dutch painting.

It wasn’t just that Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Frans Hals worked in this era it was that there was an entire, large industry devoted to producing artworks. The volume of cheap and cheerful paintings in circulation was massive, and even ordinary people routinely had some art to adorn their modest dwellings.

Once a painter had made his name, he usually opened up a workshop whereby lesser painters and apprentices churned out the basic elements of a painting and then he added the finishing, skillful touches at the end.

Tulip sellers commissioned books of tulip paintings. These were detailed, intricate still lifes of tulips, but often with a little flair such as an exotic insect or a colorful Turkish vase thrown in. There might be a hundred or more paintings per book – one painting per type of tulip in stock. The sellers were able to get away with paying very little and yet getting great work. Rembrandt’s teacher, van Swanenburch, took some work and was paid the equivalent of a large loaf of bread per painting.

The smart sellers also omitted the price of tulips from their catalogs. That way you could revise it upwards or downwards depending on who you were pitching and how badly you wanted to make a sale.

It followed that if the industry had grown, so too had the stock of tulip bulbs that could be traded. The original crop of tulips that had been pilfered from Clusius and planted in and around Haarlem had doubled five times by the late 1620s. Fields of tulips could now also be seen in the countryside just outside of Alkmaar, Gouda, Rotterdam, Gouda, Hoorn, and Utrecht.

The top tier of bulbs was bought by the very wealthy of the United Provinces (and sometimes further afield) and traded by long-established connoisseurs. One rung down there were plenty of varieties that were still highly sought-after, and these were grown and sold by enterprising laborers, artisans and peasants.

Amsterdam was the birthplace of modern finance. It housed the world’s first stock exchange, currency exchange and pioneered techniques in risk management that we take for granted today.

If you invested in a ship to go to the Far East in search of booty, it was either boom if it returned or bust if it failed to, and back then about one in five ships did not return. However, if you split your investment over ten ships then you had essentially eliminated the risk and guaranteed yourself a healthy return (probably about 300%).

They were an enterprising and mercantile bunch, those early Dutch. The people who first traded those shares in the Dutch East India Company would congregate on bridges when it was dry and in churches when it was wetland was too scarce for a property to be considered sacred seven days a week. That industry matured and eventually, they were able to build themselves a dedicated building – a place where stocks could be exchanged.

Similarly, the tulip traders needed a place where they could physically meet and conduct business. They were a more rag-tag, working-class bunch. The churches wouldn’t have them and there was no chance of them commissioning their own exchange building. So, they just met in taverns instead.

By now we’re in the 1630s. At that point, a lot of beer was drunk in The Netherlands. In Haarlem, there were 30,000 inhabitants and 120,000 pints of beer were drunk each day. A lot of that was weak beer, but it was drunk instead of water and was consumed by adults and children alike.

Imagine, then, a rowdy crowd in a tavern, there because they’ve decided to take a bit of a punt in this new-fangled tulips trade. This tavern is smoky and found on the outskirts of Haarlem and the roads that lead to it are pitch black. You’ve come to buy or sell tulip bulbs and your spirits are high. You’ll take a pint of the double strength beer, and then another.

Every time a lot of bulbs was put up for auction the seller paid a commission and this fee was immediately used to buy wine for everyone present. The actual amount of this wine money depended on the price of the winning bid, but even if the lot didn’t sell the seller still had to pay a minimum amount. It encouraged people to sell – and to drink.

Trading happened in Amsterdam too, of course, and Utrecht, Alkmaar, and many other towns and cities all over the United Provinces. There was money to be made in tulips. Originally they were sold by the bulb but as the trade increased they both multiplied and divided the unit of trade.

Cheap, single-colored tulips had always been omitted from the excitement of tulip trading in taverns but as more and more people entered the market, the demand for these grew too. It made no sense to sell these cheap flowers by the bulb, so instead, they were sold by the bed – a poorly defined term that varied from city to city.

Conversely, expensive tulips needed a more specific unit of measurement than a single bulb. One never knew in autumn when they were being sold a bulb just how large or small it would be the next spring when it was lifted. The sums of money could be quite large and so would be the ill-feeling if your bulb was smaller than anticipated.

They devised a new measurement, the ace. It was the equivalent of one-twentieth of a gram and the final sale price would depend on the actual size of the bulb. It made trading expensive bulbs fairer, but also encouraged sales.

What did people earn back then and how much could be made from trading tulips? The aforementioned Adriaen Pauw, of the elite, was worth about 350,000 guilders. This was an obscene amount, far removed from reality for ordinary people. A relatively well-off person such as a shop owner might make 500 to 1000 guilder a year, however, the vast majority of artisans made about 300 – 500 guilders a year. In a family where both parents worked – he as a blacksmith for example and she as a maid – and where they were thrifty and not given to alcoholic extravagances a family might save 20 to 50 guilders a year.

Before the mid 1630s it’s hard to find specific prices of tulips other than the rarest, most expensive varieties. A blacksmith or cooper entering the tulip trade wouldn’t have been able to trade these. There is a report from Haarlem in 1611 of four beds of rather ordinary tulips being sold for 200 guilders. Almost an entire year’s salary for many people. The next year the same purchaser acquired two more beds for 450 guilders.

This was the very bottom end of the market, and profits escalated quickly as soon as you got your hands on fancier bulbs. For ordinary working folk with either a bit of the gamble or entrepreneur about them, tulip trading offered the lure of a get-affluent-quick scheme.

Prices – and profits – rose steadily, and in 1633 something unusual happened. A rather elegant house in the provincial city of Hoorn was sold for three rare tulip bulbs. Tulips were now being used as currency. Word of this sale got out and it inspired some copy-cats: A Frisian farmhouse and farmlands were sold for a parcel of bulbs. Something was economically-a-stirring.

The Market Heats Up

This all sounds very modern and Wall Street Journal, but back then they weren’t that far from removed from the Middle Ages either. The Bubonic Plague that decimated Europe’s population in the 1300s would, in the following centuries, return every once in a while and settle down in a corner of Europe wreaking havoc for a while.

It came to The Netherlands in 1633 and stuck around for a few years – accounts variously say it lasted for two, three or four years. Death made itself known to everyone. In Haarlem alone it killed 8,000 people –one in eight of the population, so even if you escaped some of your nearest and dearest, unfortunately, didn’t.

It was at this very time that the number of people cramming into the smoky, boozy taverns to speculate on tulips began growing precipitously. A convincing theory says that the plague itself caused the increase. Fatalism was in the air, death stalked you at every corner so if you’re going to live you may as well strive to live as large as you can. The decrease in population made for a labor shortage, an increase in wages and gave ordinary people a bit more room to gather together some savings. They were heady times.

The number of trading days per year was quite small – just a few months in summer, after the tulips had been harvested but before the next ones are planted. 1633 was too soon for the influx to begin – the plague had barely made itself felt before the tulips were planted. 1634 was the year of the large increase in traders and trade. Up to this point the people trading generally had at the very least a modicum of knowledge of tulips and how they grow. Now the pendulum had swung firmly away and these somewhat knowledgeable people were vastly outnumbered by people who purely wanted to turn a profit.

Let me clarify how a deal was conducted. After a price had been agreed at auction, the buyer paid a deposit, generally 5%-10% of the purchase price or estimated purchase price if buying by the ace. He was then given the contract or note that guaranteed him his crop, and in spring the bulbs were lifted and he paid the remaining 90%-95% of the price.

In spring 1635 the crop was lifted, accounts settled and wealth increased among those who had sold. Some nice fat guilders now to their name, and where they would previously have had a watery hutspot now they might dine on pork chops cooked in rich butter. And perhaps they would have bought that most luxurious of things – an actual bed – as opposed to a cot or straw placed on a floor.

In the autumn of 1635, men – and probably a few women – crowded once more into taverns all across The Netherlands with an appetite for profit. The beer flowed freely, followed by wine every time a trade was slated.

Business was brisk – fevered in fact, with contracts changing hands faster than ever. And then in some tavern in some part of the country – we don’t know its name or where it was – someone realized that he could, in fact, offer the person who had won the contract for a crop of bulbs, more money than the first person had bid and then they’d have the crop in the spring.

Then another trader realized that he could do the same with the second person to own the contract, and then a fourth realized they could lever the contract from the third trader with an even bigger bid. And so on, for a fifth, sixth or seventh owner of the contract.

This type of trading caught on quickly, and spontaneously a futures market in tulips had developed in the United Provinces. It wasn’t the first time that a futures market had developed in Amsterdam. It had happened in various commodities – like timber, for example. The authorities had been wary then, but those markets were regulated so things never spiraled badly out of control. Not only was the tulip market not regulated but it was fuelled by alcohol.

Let’s say you had cobbled together savings of 100 guilders, at auction you could – if your bid was successful – buy 10 tulips each valued at 100 guilders because you only had to pay a deposit of 10%. The way prices had risen in previous years you could easily expect to double your profits (at a conservative guess). Come harvest time you collect your bulbs, sell them for 2000 guilders, pay off the 1000 you owe and are left with 1000 guilders. This was about three years pay for an ordinary worker.

Conversely, if you couldn’t find a buyer for any of your ten bulbs then you had lost your 100 guilders deposit and owed 900 more. Again, about three years salary. But hey, that’s never going to happen, so let’s just stop depressing everybody.

On February 5, 1637, an auction was held in Alkmaar in a guildhall. Wouter Winkel, an innkeeper, had just passed away and his collection of bulbs was being auctioned off for the benefit of his children. Their mother died some years previously, and because of their father’s cleverness and good fortune in the tulip trade, they would at least be able to avoid the economic hardship that otherwise befell orphans.

Winkel embodied the ideal of social mobility that ordinary people could strive for. That few would ever attain it was to an extent beside the point, you could at least imagine it – which is something that the Brits, French, and Germans couldn’t do. An innkeeper was a rather ordinary station to hold in life, though you might have a few more guilders coming in than a baker or cobbler. Winkel had gotten into the tulip trade early and had managed to build an elite collection of bulbs. The sort that Adriaen Pauw would have wanted to own (though we don’t know if he had any agent present at the auction).

People came from all over the country to bid on these bulbs. The local inns and hotels did a roaring trade, and then the bidding began. The jewel in the crown was an Admiral van Enkuizen (in The Netherlands where there was no monarchy valuable flowers were given names like Admiral or General) and it sold for 5200 guilders.

The same buyer spent a total of 21,000 guilders on flowers – enough to buy two large canal houses in Amsterdam. In total, seventy lots of tulips constituting about 100 or slightly more bulbs sold for a total of 90,000 guilders. That would be about €6m – €15m in today’s money. And that was just a single auction.

In the taverns, prices rose in more or less the same proportion. Demand was skyrocketing, so much that even the common bulbs, the vodderij (rags) which had only in recent years had seen some level of speculation, doubled, trebled and quadrupled in value.

Yellow Crowns were cheap tulips, pleasant in and of themselves, but with no great appeal to anyone who wanted unusual tulips or valuable ones. In September 1636, a parcel of these went for 20 guilders and by the end of January 1637, they now sold for 1200 guilders. This twenty-fold appreciation was not the exception it was the norm.

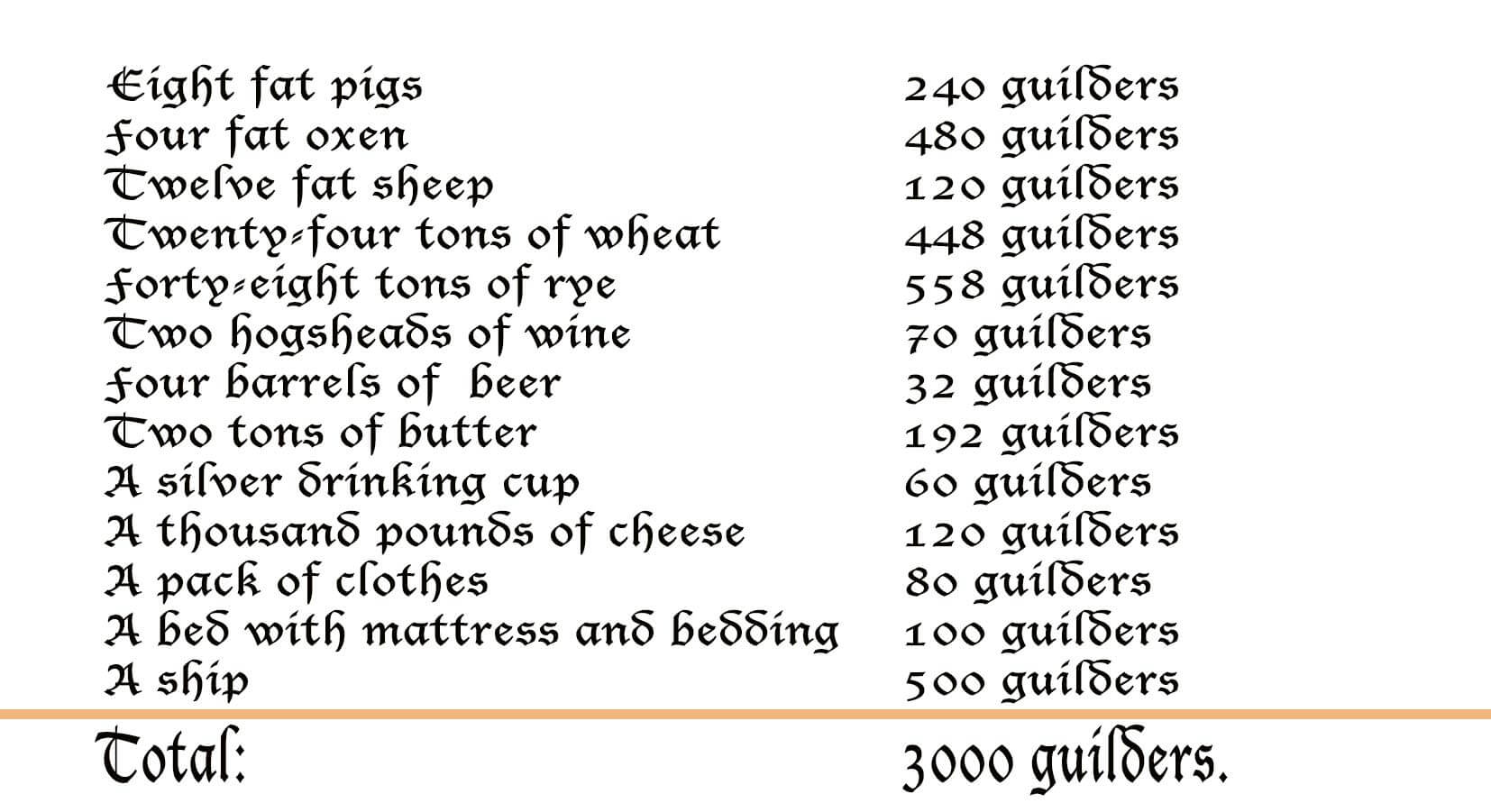

Many bulbs sold for 3000 guilders or more, and here is what you could have bought for the same amount:

These auctions were happening all over the country. A social mania had taken hold. Tales of vast profits brought more speculators. In early February 1637, the regular traders met in one of Haarlem’s taverns, and the first lot of tulips was offered at 1250 guilders.

Unusually, nobody bid and so the price came down. 1100 guilders, 1000, 900. Still, nobody bit and the atmosphere in the room changed irrevocably. The boozy good cheer was replaced with caution, awkwardness, fear. Not a single tulip was sold that night.

The bubble had just burst.

Technically there was not one tulip market in Holland then but very many. It took time for people – and news – to travel from town to town, and each center valued tulips in slightly different ways. The night that no bulbs sold in Haarlem, still saw successful trading in the likes of Amsterdam and Rotterdam. However, over the coming days, news spread and within about two weeks the tulip market had collapsed nationwide.

What had happened? Quite simply, the starting price of tulips had risen so grotesquely that nobody who wanted the tulips for themselves – the end user – was bidding. It was purely speculators and they had unknowingly reached the tipping point where bidders no longer felt they could make money. They simply stopped bidding and the market collapsed.

What of the people who had previously bought contracts that very winter? The ones who successfully bid thousands of guilders for a single bulb or parcel of bulbs? Well, those were valid contracts but now they faced inevitable ruin, for when those bulbs were lifted in spring they’d owe the full amount and would have nobody to sell them on to.

Furthermore, there was a whole chain of people who owed money. The seventh person to buy the contract owed the sixth, who owned the fifth all the way back to the grower. That was six people (for example) who faced bankruptcy and a considerably less affluent grower. There were thousands of such outstanding contracts around the country.

Once lifting time came round, a kind of inertia took hold – every party to a futures contract kind of not doing anything – not collecting their crop and not paying, and soon it began to seem like people would simply default on their obligations.

There was uproar, especially amongst the growers. Court cases ensued and in different jurisdictions. But the city courts deferred to the municipal courts who deferred to the national court, but then the national court said, ‘well, this should be sorted out on a local level.’ Nobody wanted anything to do with it.

Return To Normality

Eventually, after a year or two of wrangling and bitter recriminations, a legal resolution was put in place. The contracts, which had been de facto futures contracts were now converted into optional contracts. The buyer could take up the full contract or opt to cancel the contract by paying a fee of 3.5%.

Everyone chose the latter option.

There were many annoyed growers, but it was the most pragmatic option available to this most pragmatic of nations. These growers missed out on big profits but they didn’t really incur any losses and got a modest fee to compensate to some extent. And many men – and their families – were able to avoid bankruptcy and destitution that would have made matters worse for their communities.

About 3000 chastened traders were implicated in the mania but it was out of a total population of two million. And once the onerous debts of these people were essentially canceled it further softened the blow to the economy. In fact, the Tulip Mania ended up having very little effect on the economy. The entire century made up the Golden Age and we were only in 1637 when the bubble burst.

The story of the Tulip Mania is one that is vaguely familiar to many people, and they often associate it with economic disaster. The tale was popularised by the Scottish writer Charles Mackay in the 1800s through his seminal book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. However, his primary source was three religious pamphlets written just after the mania which wanted to teach people a lesson and elided all of the nuances of the mania and exaggerated the effect it had on the country.

After the mania subsisted the actual market for tulips did not disappear, it merely retreated to normal levels. The very rich still wanted rare tulips for their gardens and they paid accordingly – though nowhere near the levels that were being agreed on during the winter of 1637. And because of the French court in the 1610s, and most probably because of the mania too, the tulip was still a desirable flower around Europe. By the 1640s, the tulip fields that had spread slowly out from Haarlem were the source of most of Europe’s tulip bulbs. The country’s top three exports were gin, herring, and tulips. Echt Nederlands, indeed.

Other Obsessions

If you think, that a financial bubble in flowers was a complete freak you’d be somewhat wrong. Other varieties became fashionable around Europe for periods, including the hyacinth in The Netherlands in the early 1700s. It was similarly slow to grow and given it was newly fashionable prices appreciated rapidly, though not to the same exponential level as with tulips. This second bubble burst in 1737, a nice, round 100 years after the Tulip Mania.

This particular form of floral mania wasn’t exclusive to the Dutch, the Ottoman Empire would experience its own version in the early 1700s. The Turks had never lost their love for the flower and at this point, the empire had entered decadent decline – that point where a once dominant power masks acceptance of its diminished status with hedonistic extravagances.

In their case, it was spectacular tulip festivals. The type that was planned a year in advance, lasted for weeks, where the clothes of guests had to complement the tulips and at night the gardens were illuminated by candles fixed onto the backs of tortoises.

Yes, that extravagant.

Today, when you come to visit the Keukenhof Gardens there are nearby country roads that will take you past the working tulip fields that owe their existence to Clusius and the thieves who robbed him. I hope that if I’ve kept you reading this long that I’ve earned the liberty of promoting our tour for a moment.

The big tour buses that cram you in are unlikely to take these routes, but with our nimble 8-seat vehicle we’ll spin happily through them… And on that suitably mercantile note, it’s time to say doei.

These tulip fields – in the area near Keukenhof – owe their existence to the theft of Clusius’ bulbs in the 1590s.

Click this link for info about our Online Tulip Field Tour that runs in 2021

I’ve relied heavily on two books, Tulipomania by Mike Dash and The Tulip by Anne Pavord as well as some other histories and academic articles. I claim no credit for the primary research. Copyright 2017 Rory Brosnan, however you are free to share this article. If you’d like to use it on a website or publication please contact That Dam Guide.